Back

Back

Among the things I began to do with all my spare time when I retired in 1999, was reading more in the realm of quantum mechanics, a subject that had always interested me. At about the same time, some accident put in my hands a book my wife had brought back with her from Taiwan, What the Buddha Taught, a classic exposition by Walpola Rahula, completed in Paris in 1958, only half a dozen years before Doris and I got to know each other there. I had paid no attention to it for our 11 years living in Taipei, but now it was a sudden eye opener. The mutual reinforcement of the two outlooks, QM and Buddhism, the many resonances of thought appealed to me immediately, and I began to read avidly in both worlds. Books like The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra, and many others. One consequence of this renaissance for me was that I started writing an explanation to myself of what I was discovering.

Here are the first 13 pages (in-hand style) of that essay, written in 2001. I gave up the writing of it another dozen pages along (where I struggled with the problems of defining and understanding life as biologists understand it) – not merely because I knew I was so far in over my head, but also because my reading had by then shown me that many others had put it all together already, and with great clarity and vastly more erudition than I command.

This up-dated version uses marginal notes to expand some ideas and give references.

I provide these pages to whatever reader might someday come along, and that definitely includes myself, in part just because they lead up to a mystical experience I had one evening along a lake in the Upper Peninsula, one that fits with those discussed in the earlier page, Dr. Taylor and near death 1.

Reading R. C. Zaehner’s study of Hinduism gives me the impression that they’ve got the nature of things about right: “So far as it is at all possible to summarize the teachings of the Upanishads we should say that they identify the deepest level of the subjective ‘I’ with the ground of the objective universe.”

I used to think the deepest level of my subjective existence was some maelstrom of unconscious tendencies, a storm that incredibly perceptive authors like Dostoevsky and Kafka could help me peer into and clarify to some extent. I still find those authors useful and perceptive, but my experience of life is taking me elsewhere now. As for the objective universe, although I conceded that I was part of it, my basic feeling was that it was also something I peered into from outside. Here my guides were the equally perceptive scientists. I still stand in respectful awe before their accomplishments, but the more of them I read, the more I realize that I can’t just stand outside and observe anymore. In fact, I have especially come to feel that the universe and I are more interesting for our connectedness.

Subjective Reality

The usual flow of our subjective experience does not run very deep. It is filled with issues of self and status, and our sense of who we are is confined to the window of thinking and feeling we are looking through at any one moment. I recall one summer in Upper Michigan when my wife sharply corrected my management of our son in front of the two friends we were sharing a cabin with. This to me embarrassing moment instantly created in me a painful sense of alienation from and anger at the wife, as well as a darker and troubling sense of humiliation. I sulked and moped through several hours that included a long drive by myself and a determination to sleep alone that night. In fact I ended up lying outside trying to sleep under the stars. Brilliant stars on a moonless night with a delicate breeze rustling the needles of those dark conifers standing guard all around my spot. I stared resentfully into the spaces between the stars, feeling very sorry for myself. And it dawned upon me quite gradually that those spaces were unfathomably vast and the tiny sparks of light huge universes of fire exploding in unending cascades of energy that made no difference at all to the timeless darkness between them. The problems of one Bob Krieckhaus, whose wife had just lapsed into a moment of tactlessness somewhere in a woods on the northern hemisphere of a small planet turning about an ordinary sun wandering somewhere in one of millions and millions of galaxies flashing through the void to unknown and unimaginable ends — those problems suddenly lost all importance to me. In fact, I myself lost all importance to me. I experienced a moment of personal annihilation, but surely universal truth, and went back in and made it up with my wife.

I need to stress that this conciliatory move was not based on any sense of my own foolishness in the matter, nor on any remorse felt or insight achieved into the right or wrong of child care or conjugal relations. It was based on a sudden and overwhelming sense of my own insignificance, and the insignificance of all human problems in light of my (strangely, if you think about it) non-threatening experience under the stars. And that was a moment of subjective experience quite different from my usual — not, I think, a moment of experiencing the deepest level of subjective experience, but definitely a moment of inner experience at a more basic and important level of my being in life than the usual moments one has.

The usual moments are pretty lame. I like E. F. Schumacher’s treatment of this subject when he is discussing self-knowledge, that ancient prerequisite to all further studies:

Now, self-awareness is closely related to the power of attention, or perhaps I should say to the power of directing attention. My attention is often or even most of the time captured by outside forces which I may or may not have chosen myself — sounds, colors, etc. — or else by forces inside myself — expectations, fears, worries, interests, etc. When it is so captured, I function very much like a machine; I am not doing things: they simply happen. All the time there is, however, the possibility that I might take the matter in hand, and quite freely and deliberately direct my attention to something entirely of my own choosing, something that does not capture me but is to be captured by me.

My moment of insight under the stars was not chosen by me, of course. I was captured, machine-like as we mostly are, by the location and the context. However, this unusual context and moment dropped me out of my usual level of experience down into a layer of being that I found to have great significance at the time and have often had recourse to later, when I have in fact taken matters in hand and quite freely and deliberately directed my attention to this aspect of reality.

There seems to be some link between “deeper” and freer. I feel more authentic, more real, when my subjective experience is less manipulated by that constant stream of conventional forces that we all swim in by the necessity of our being social creatures at this time and place. Those forces are both internal and external — our upbringing has given us each a particular syndrome of “expectations, fear, worries, interests, etc.” that drives our responses to external events which themselves generally take a form of human impulse: our spouse’s fear, our colleague’s judgment or ambition, the TV’s exciting tone. And the ubiquity and intensity of these forces are what capture us, as Schumacher says, and leave us functioning like machines in a world where we generally just respond to things that happen to us and ride along on a wave of ever-changing fashion.

Having retired a little early from my usual workworld, so constantly intrusive into my subjective experience, I find it quite satisfying to rest quietly on the shore trying to follow Thoreau’s famous dictum and live my life deliberately. One choice I make is to investigate those layers of my inner experience that open up to me when I am more free from conventional pressures. This essay is an important part of the examination I am making. My beginning is to sort out some of the layers I have lived in, looking for those less governed by ordinary worldly pressures because they offer glimpses of a world of experience that seems to be deeper and more real, a world I would like to live in more often.

Back in 1986 I was flowing with one of the waves that had been washing through my academic world for some time, a movement towards using outdoor activities with groups of high schoolers to create special experiences for them that would tend to foster what we thought were good, socially useful attitudes as well as significant personal enrichment. The ideal of the solo time was among those in the air then. And this led to my deciding on a 7-day solo backpack into the Gila Mountains of southwest New Mexico one summer. Sitting in the later afternoon on the side of a deep green canyon then, I listened to a distant owl and discovered a vole peering at me from beneath some grasses. It was very peaceful, quiet of course, and I had been without human contact for some days. Those intrusive manipulations of the school world that push one’s inner experience into calculating scenarios for dealing with vanity, humiliation, achievement, failure and the like, they had faded largely away. Thunder began to happen, it darkened quite a lot, and looking up into a tall fir I chanced to see an accipiter settled in for the coming night quite as I was. This concentrated my awareness sharply into a smiling-solemn sense of oneness with the bird. I was moved to try to capture this moment in writing and wrote the first simply and sincerely expressive poem of my life at this time.

New Mexico Solo Notes

Parked silent on one dark limb

Of that tall-standing dead fir,

A gray accipiter,

Hunched high above Spruce Creek Valley,

Silhouetted, doesn’t move.

Beyond him all his domain, and my wonder.

Massive walls of spruce and fir fall and rise

Against the rainy evening sky,

From which now thunder rolls its warning

Off the distant falling walls.

At my feet, a small fire, the universe.

Moments of subjective experience like these are times of harmony and union with the outer world, times when the outer world combines with the inner in an inextricable manner and one forgets her own otherness. This seems at first sight rather opposite from the time in Michigan under the stars, which placed me in an entirely diminished, a vanished position vis-à-vis an overwhelmingly remote and “entirely other” universe, but there is a common element, too — the dropping out from the inner experience of the superiorly situated, confidently distinct self.

It turns out that modern neuroscience has a word for this. In the terminology of Sharon Begley in Newsweek Magazine, there is a quieting of activity in an area of the brain’s upper parietal lobes “nicknamed the ‘orientation association area.’” This happens, for instance, on occasions such as the one she opens her report with:

One Sunday morning in March, 19 years ago, as Dr. James Austin waited for a train in London, he glanced away from the tracks toward the river Thames. The neurologist—who was spending a sabbatical year in England—saw nothing out of the ordinary: the grimy Underground station, a few dingy buildings, some pale gray sky. He was thinking, a bit absent-mindedly, about the Zen Buddhist retreat he was headed toward. And then Austin suddenly felt a sense of enlightenment unlike anything he had ever experienced. His sense of individual existence, of separateness from the physical world around him, evaporated like morning mist in a bright dawn. He saw things “as they really are,” he recalls. The sense of “I, me, mine” disappeared. “Time was not present,” he says. “I had a sense of eternity. My old yearnings, loathings, fear of death and insinuations of selfhood vanished. I had been graced by a comprehension of the ultimate nature of things.”

Begley gives another doctor’s description of a similar moment of subjective experience:

There was a feeling of energy centered within me … going out to infinite space and returning … There was a relaxing of the dualistic mind, and an intense feeling of love. I felt a profound letting go of the boundaries around me, and a connection with some kind of energy and state of being that had a quality of clarity, transparency and joy. I felt a deep and profound sense of connection to everything, recognizing that there never was a true separation at all.

This person, Dr. Michael J. Baime, who had been practicing Tibetan Buddhist meditation since he was 14, permitted his brain to be examined at a moment like this by some fancy equipment that returned results that suggest the analysis that a certain part of the parietal lobes is largely “turned off” at these times, a part that “processes information about space and time, and the orientation of the body in space. It determines where the body ends and the rest of the world begins.”

These two subjective experiences return us to Zaehner’s statement of the core of the Upanishads: “They identify the deepest level of the subjective ‘I’ with the ground of the objective universe.” But their placement in the context of scientific experiments on the brain also raises the question of how we can know what is real, and whether we can trust these unitary subjective experiences to be as faithfully responsive to and representative of What is Out There as our more customary subjective readings. There may be a link between deeper and freer, but what is meant by “deeper” may and does to some appear as a distortion of reality achieved by “freeing” oneself from common sense.

Scientific Reality

To know what common sense tells us, of course, we must free ourselves of those prejudices, superstitions and false assumptions that most people concede do at least color other people’s common sense judgments. Science, attempting to limit itself rigorously to what objective measurement and experiment can say, is our best hope for agreement about the nature of at least some of reality. And the word from on high has become disturbingly non-commonsensical of late.

In an issue of Scientific American that found its way into my mail box as I was first writing this, I read that in the process of freezing light dead in its path, the people who work with Lene Vestergaard Hau at the Rowland Institute of Science at Cambridge, Mass., do the following:

The transparency-inducing beam, or coupling beam, is tuned to the energy difference between states 2 and 3 [of the valence electron of the sodium atoms they are using]. The atoms, in state 1, cannot absorb this beam. As the light of the probe pulse, tuned to state 3, arrives, the two beams shift the atoms to a quantum superposition of states 1 and 2, meaning that each atom is in both states at once. [Emphasis added.]

There was a time, not long ago, when I would not have had to add the emphasis because the author would not have taken it for granted that none of us would bat an eye at the thought of placing one thing in two places at once. That’s one physical thing (a bunch of atoms) and two physical energy states. The atoms (their valence electrons) are, as it were, both higher and lower at the same time.

Because Ms. Hau is dealing with tiny things we can’t see with our eyes, we may think her work is a distortion of reality that is of relevance only to the physicist of Quantum Mechanics, not to us, not to the reality that our subjective experience generally corresponds to. Certainly that is what I did in my life for a long time with troublingly non-standard-issue information. Most UFO sightings can be rejected out of hand as illusional or delusional, and the few that cannot we can just ignore on the grounds that they haven’t happened to us, most educated people don’t take them seriously, and it just doesn’t make any difference in our lives. However, there is one famous experiment in the physics of QM that has always troubled me, and that I have never quite been able to disregard. It is usually called the double slit experiment, first performed, but in a non-disturbing way, by Thomas Young in 1807.

The original experiment simply showed that light is, as we all know now, a wave phenomenon. If you project light on a wall through two fairly close-together slits in a blind, you get an interference pattern typical of waves on the wall on the other side. You don’t get two slits of photon hits aligned with the two slits in the blind. My recollection is that this experiment resolved the scientific question at that time of whether light was particulate or wave-like in nature. Then early in this century it was shown (by Einstein and Compton) that light is definitely composed of particles, called photons.

But, of course, they thought, there’s got to be something wrong here. Light can’t very well be both particles and waves. So they went back to the double-slit experiment and tried closing now one, now the other slit. They got two corresponding stripes on the wall, just what you’d expect to get from particles. But why, with two open at the same time did they get the interference pattern?

Maybe, they thought, the particles bump into each other on the other side of the slits in such a way that the interference pattern is produced. So, to check up on this possibility, and as by now technology had advanced far enough to permit this, they shot single particles, one at a time, at the two-slit screen. Each particle would make its mark on the wall (or photographic plate or whatever) and stay there (as its mark...) while the others were coming in, one at a time. And lo, after an hour or so of single particle shots, they STILL got the interference pattern.

You can think of it this way, as the photon approaches the blind, it sees either one or two slits ahead of it, and if there’s only one, it says, Fine, I’ll be a particle, but if there’re two, its says, Nope, I’ll be a wave.

At this point, famously, famous scientists have repeatedly said, if you think this makes any sense at all, you haven’t understood the experiment. The reassuring news there, is always that the scientists say they don’t understand either. Well ...

OK, now comes a further complication. Actually this is, if you’ll permit the expression, the real stunner. They decided to take a picture of the photons or electrons (the experiment works the same for either) as they went through the slits. (OK, not exactly a picture, but they figured out a way to know which slit, if either, the particle went through. And by the way, at the wall, on the photographic plate, the patterns are always made up of little particle strike points, whether they collectively constitute an interference pattern or not.)

And now, here’s what happens – if the experimenters know which slit the particles go through, then they behave like particles should and don’t make the interference pattern.

Repeating: if the scientists watch the particles, they behave well, like particles, but if nobody’s watching, they act like waves.

>>> >>> >>> >>>

Now this paradox does not present itself as some consequence of your interfering with the light when you measure it. My books tell me that some people use the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which is another formulation of or response to this troubling experiment — to explain the trouble away by suggesting that it’s just a matter of our clumsy means of observation. If we check the particle’s passage by any measurement at all, we disturb it as we check it, adding momentum, changing its position etc. For these people, nature may still be common sense natural.

But the teachers and scientists who themselves uncovered this trouble (Bohr, Heisenberg, Schrödinger and the rest, as well as our most prominent scientists right now) were and remain thoroughly baffled by it, and do not remotely think it comports consistently with either common sense or physics as they otherwise know it. This doesn’t mean, of course, that they give up physics and become psychics. They go right along describing, experimenting with, and predicting natural relationships and events. If they want to stop light, hold it a while, then let it go so they can make a super fast computer, fine, they just hold their sodium atoms in a state of superposition and get on with it. But when they want to think more philosophically, they say things like MIT professor Alan Lightman, whose exposition of the double-slit experiment I have been using, and whose summary observations I will quote here:

The contradiction between the [checking and not-checking] experiments is the enigma of the wave-particle duality of light and, as we will show, the duality of all nature. When we don’t check to see which slit each photon goes through, each photon behaves as if it went through both slits at the same time, as a spread-out wave would do. When we do check, each photon goes through either one slit or the other and behaves as a particle of light. Light behaves sometimes as a wave and sometimes as a particle. Astoundingly, and against all common sense, the behavior that occurs in a given experiment depends on what the experimenter chooses to measure. Evidently, the observer, and the knowledge sought by the observer, play some kind of fundamental role in the properties of the thing observed. The observer is somehow part of the system. These results call into question the long-held notion of an external reality, outside and independent of the observer. There is nothing more profound and disturbing in all of physics.

“Long-held,” but not always-held. The view of the Upanishads that identifies the deepest level of the subjective “I” with the ground of the objective universe is both older than the nineteenth-century scientific paradigm (so disturbed by these results) and apparently quite compatible with the QM twentieth-century view. And if our medical doctors attribute their mystical experiences of union with the world to a diminution of activity in the superior parietal association cortex, perhaps we should suspend our common-sensical disbelief and ask how we can get the same results with our own s. p. a. c.

In fact, though, I know of one way we can get a disturbingly strange non-common-sensical experience with “reality” without either messing with our parietal lobes or watching photons passing through slits in dark rooms, but just by looking at pictures projected on a screen. No drugs or long cross-legged sitting times required.

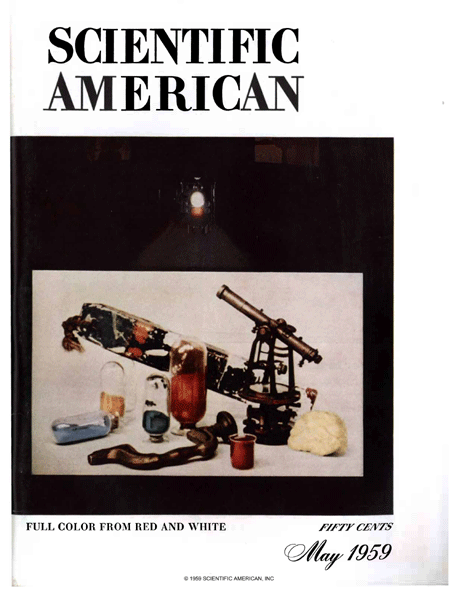

I have never forgotten reading about this experiment in the May 1959 issue of Scientific American.

Edwin Land (of Polaroid fame) reported there on the strange results he and his colleagues had discovered when projecting images of a color scene onto a screen in various ways. They had made three transparencies of the scene by photographing it in black and white through red, green and blue filters. By projecting the resulting three black and white transparencies onto a screen through red, green and blue filters again, they produced a full-color version of the original scene. When an accident occurred, someone knocking off the green filter so they were looking at the screen image created by a red-filtered image, a blue-filtered one, and a non-filtered straight grayscale image, the results were oddly not significantly different from the full-color version they had had with the three filters at the same time. Surprised, they experimented with various light intensities and even tried removing another color filter… The long and short of it was this: projecting the black and white images onto the screen at the same time through no filter and through the red one, THEY STILL SAW A FULL-COLOR IMAGE.

Recap: you project a black and white grayscale image without a filter onto a screen and you get a black and white grayscale image. You project a grayscale image through a red filter onto a screen and you get a pink image. But when you do both together, you get full color. Although the result ought to be, and “in fact” in “reality” really is just a diluted pink version of the image, what one sees is ALL the colors of the original full-color slide. (There is a 1985 BBC documentary on these experiments that is remarkably thorough and rather demanding. It’s called Colorful Notions and can be found on YouTube and here at Vimeo in one piece.)

If our minds create subjective experiences of colors that are not physically present in what we are looking at, and if light projects onto a screen as a wave interference pattern or simple stripes depending on what we choose to look for, how confident can we be of our status at any time as objective observer looking out upon a world separate from ourselves? Not very, I would say. At the deepest level of the subjective ‘I’ (not a level we are generally much aware of) we are at least partially merged with the ground of the objective universe.

A Little Lower Layer

Let us, then, free ourselves from the Victorian fetters of scientific reductionism and accept unitary subjective experience as a significant part of our knowing. Dr. Baime knows the sound of mitral and tricuspid valves closing, and he knows an experience of “a deep and profound sense of connection to everything, recognizing that there never was a true separation at all.” The former item of knowledge he shares with other health professionals all over the world, the latter he shares with mystics of many persuasions, places and times.

Among the sharers of the Drs Austin and Baime’s mystic experience is Aldous Huxley. The description he gives us of his peyote/mescaline experience in The Doors of Perception brings powerfully to the reader’s mind the strange otherness of the world seen by mystics, and his reflection on that world brings a conceptual clarity to the relationship between that world and our more normal world.

Place and distance cease to be of much interest. The mind does its perceiving in terms of intensity of existence, profundity of significance, relationships within a pattern…. Space was still there; but it had lost its predominance. The mind was primarily concerned, not with measures and locations, but with being and meaning.

I was looking at my furniture, not as the utilitarian who has to sit on chairs, to write at desks and tables, and not as the cameraman or scientific recorder, but as the pure aesthete whose concern is only with forms and their relationships within the field of vision or the picture space. But as I looked, this purely aesthetic, Cubist’s eye view gave place to what I can only describe as the sacramental vision of reality.

I was seeing… the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence. … Istigkeit — wasn’t that the word Meister Eckhart liked to use? “Is-ness.” The Being of Platonic philosophy — except that Plato seems to have made the enormous, the grotesque mistake of separating Being from becoming and identifying it with the mathematical abstraction of the Idea. He could never, poor fellow, have seen a bunch of flowers shining with their own inner light and all but quivering under the pressure of the significance with which they were charged; could never have perceived that what rose and iris and carnation so intensely signified was nothing more, and nothing less, than what they were — a transience that was yet eternal life, a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being, a bundle of minute, unique particulars in which by some unspeakable and yet self-evident paradox, was to be seen the divine source of all existence.

Reflecting on my experience, I find myself agreeing with the eminent Cambridge philosopher, Dr. C. D. Broad, “that we should do well to consider much more seriously than we have hitherto been inclined to do the type of theory which Bergson put forward in connection with memory and sense perception. The suggestion is that the function of the brain and nervous system and sense organs is in the main eliminative and not productive. Each person is at each moment capable of remembering all that has ever happened to him and of perceiving everything that is happening everywhere in the universe. The function of the brain and nervous system is to protect us from being overwhelmed and confused by this mass of largely useless and irrelevant knowledge, by shutting out most of what we should otherwise perceive or remember at any moment, and leaving only that very small and special selection which is likely to be practically useful.”

In the mystic experience we have another kind of knowing. James Austin quotes M. Schuman on the knowing sought in the meditative tradition:

One of the basic tenets of meditation is the notion that passive awareness is a natural, elementary, and direct form of experience that is ordinarily overwhelmed and obscured by the activity of the mind. The purpose of meditation, therefore, is to allow the mind to become quiet and thereby uncover the capacity for this experience.

This formulation parallels the idea of mind as eliminative in Bergson as paraphrased by Broad. Huxley elaborates the Bergson idea:

According to such a theory, each one of us is potentially Mind at Large. But in so far as we are animals, our business is at all costs to survive. To make biological survival possible, Mind at Large has to be funneled through the reducing valve of the brain and nervous system. … To formulate and express the contents of this reduced awareness, man has invented and endlessly elaborated those symbol-systems and implicit philosophies which we call languages. Every individual is at once the beneficiary and the victim of the linguistic tradition into which he has been born — the beneficiary inasmuch as language gives access to the accumulated records of other people’s experience, the victim in so far as it confirms him in the belief that reduced awareness is the only awareness and as it bedevils his sense of reality, so that he is all too apt to take his concepts for data, his words for actual things…. Most people, most of the time, know only what comes through the reducing valve and is consecrated as genuinely real by the local language. Certain persons, however, seem to be born with a kind of by-pass that circumvents the reducing valve. In others temporary bypasses may be acquired either spontaneously, or as the result of deliberate “spiritual exercises,” or through hypnosis, or by means of drugs. Through these permanent or temporary by-passes there flows, not indeed the perception “of everything that is happening everywhere in the universe” (for the by-pass does not abolish the reducing valve, which still excludes the total content of Mind at Large), but something more than, and above all something different from, the carefully selected utilitarian material which our narrowed, individual minds regard as a complete, or at least sufficient, picture of reality.

The other kind of knowing is direct knowing, unmediated by the restrictive and defining structures of, for instance, language. This is, of course, the famous goal of Zen. Anne Bancroft relates the fundamental discovery of Dogen, the Japanese Zen master of the thirteenth century (1200-1253) when he was studying in China under Master Ju-ching:

When he overheard these words [addressed to another monk: “The practice of zazen is the dropping away of body and mind. What do you think dozing is going to accomplish?”] Dogen suddenly saw the truth: Zazen [meditation] was not a mere sitting still, it was the dynamic opening up of the Self to its own Reality directly, by letting go of all ideas about life. When life is experienced without the ego intervening, the experience is that of its true and numinous nature.

My own most complete opening up to reality was in fact mediated by a dose of mescaline provided by friends more than thirty years ago. In a safe and wooded area underneath brilliant stars on a cool summer evening beside a northern lake, I had an experience essentially identical to Huxley’s — I did not read his account until thirty years later, but my memory of this event is still very clear, and I have little to add to or qualify in his account. Like Huxley, I am not a visual person, and like him I expected some extraordinary visual experiences, and like him that is not what I got — rather that extraordinary enhancement of my sense of the being and meaningfulness of ordinary things that he describes. My strong sense at one point was that the trees and shrubs around me were stunningly and beautifully alive, and also unutterably loving, in some profound manner I had never suspected, and could only lovingly and longingly identify with. I felt as if I were simply and totally a part of this world, and to join it yet more fully and appropriately I removed my clothing and let myself fall happily into some beckoning bushes.

At this point, for better or for worse, the people around me became alarmed at my unusual activity and intervened to restore me to a more normal behavior, something that, as Huxley also indicates, is quite possible under the influence of this drug.

Since that time I have not had the opportunity of trying mescaline a second time, and I have not come even close to such an intense subjective experience of unity with a transience that was yet eternal life, a perpetual perishing that was at the same time pure Being. Still, in my retirement, secure and happy in a remote mountain setting, as I sit in frequent contemplation of and meditation in my natural surroundings, I have Wordsworthian intimations of that long-ago experience, and whereas formerly I wrote it off as a drug-produced aberration of my youth, now I regard it simply as my best and most accurate reading of the way things are.

Strongest in my rational formulation of that is a sense of being overwhelmingly absorbed, to the point of the loss of self and any personal significance, into and by the intricate, profound and completely ubiquitous presence of life in the world. This registers in subjective experience as a fact of extraordinary significance, something that must alter profoundly the entire course of one’s life henceforth, perhaps because of the stunning discovery that one is oneself completely identical with this lovely, intricate life process — not just also alive, and not just for now, but alive with, as and in this surrounding life, which is not other, but the same as oneself — and one’s self, well, one has lost that and gained the universe and eternity.

I have no inclination to join Huxley in his frequent use of terms like “sacramental” and “divine,” which my language background associates too firmly with the concept of a creator god external to this world, but I would say that my respect for, awareness and love of this vision of reality that I still have, constitutes my religion. It is out of this awareness, and by means of frequent and regular choosing to direct my subjective attention in this direction, that I deal with the prospect of my own death as well as all kinds of personal grief and loss, including the anguish I often feel about political and social events and conditions far from me as well as my own sense of failure and personal guilt. When life is experienced without the ego intervening, the experience is that of its true and numinous nature, and one is, as it were, reborn to life.

Life and Mind

Just as my subjective experiences of luminous merging with “this lovely, intricate life process” link back to Professor Zaehner’s lucid epitomization of the Upanishad teachings as identifying “the deepest level of the subjective ‘I’ with the ground of the objective universe,” so do they raise the same red flags of scientific alarm as the similar experiences of Doctors Austin and Baime: Where is the common sense of this? What has science to tell us about this life process thing?

{My further musings on this topic, starting with Jacques Monod’s great book Chance and Necessity, a firm upholding of scientific materialism, I omit because they are 1) a jump to another chapter of thought and 2) quite limited by the inadequacy of my own knowledge. See Rupert Sheldrake, above all, for a profound scientific and philosophical treatment of the puzzles of life as one understands it in biology. And, by the way, there is no general agreement among biologists as to the nature of life. One does hear this expression a lot – “an emergent property of matter.”}

In December of 2011, I began some renewed thinking along the lines of materialism versus spiritualism and created what became the Mind-Matter part of this site.

Zaehner, R. C. Hinduism. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1962. 49.

For a very modern, quantum mechanically up-to-date version of this idea, check out this supplementary page.

I am thinking of the Buddhist Middle Path doctrine of Pratitya Samutpada.

This is not to say, of course, that I did not actually feel foolish and express remorse later in the ordinary human processes of reconciliation. We move in and out of different layers of being.

To get a really, really clear exposition of this puzzle, you can’t do better than this YouTube cartoon: video. There is a subsequent experiment called the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser that places the “camera” observing which path the particles/waves take from a point AFTER they pass through the slits. Here is one video that reasons from that experiment by presenting it in very general terms. Here is the best source I have found so far to explain all the details of the Yoon-Ho Kim version of the experiment. It has the blessing of Kim himself BUT it is written for the advanced student. I have summarized that paper myself in order to make it as clear as I can — here.

The interference pattern looks like a set of stripes aligned with the slits, an odd number, the brightest in the middle and pairs diminishing in brightness moving out from there right and left.

Richard Feynman himself can be watched and listened to in a one-hour lecture explaining these facts of nature back in 1964 at Cornell University. It’s a black and white film, Feynman uses a blackboard, but it’s Feynman himself, and he uses only very elementary mathematics. At 8 minutes into the clip he notes that while people famously said that only half a dozen people understood Special Relativity when it first came out, that wasn’t really true; people who read carefully did understand fully. “On the other hand, I do believe I can safely say that no one understands quantum mechanics.”

Link.

Lightman, Alan. Great Ideas in Physics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000.